Mental health and the NHS

What's changed and what's to come?

Credit: National Archive

Credit: National Archive

Mental health today

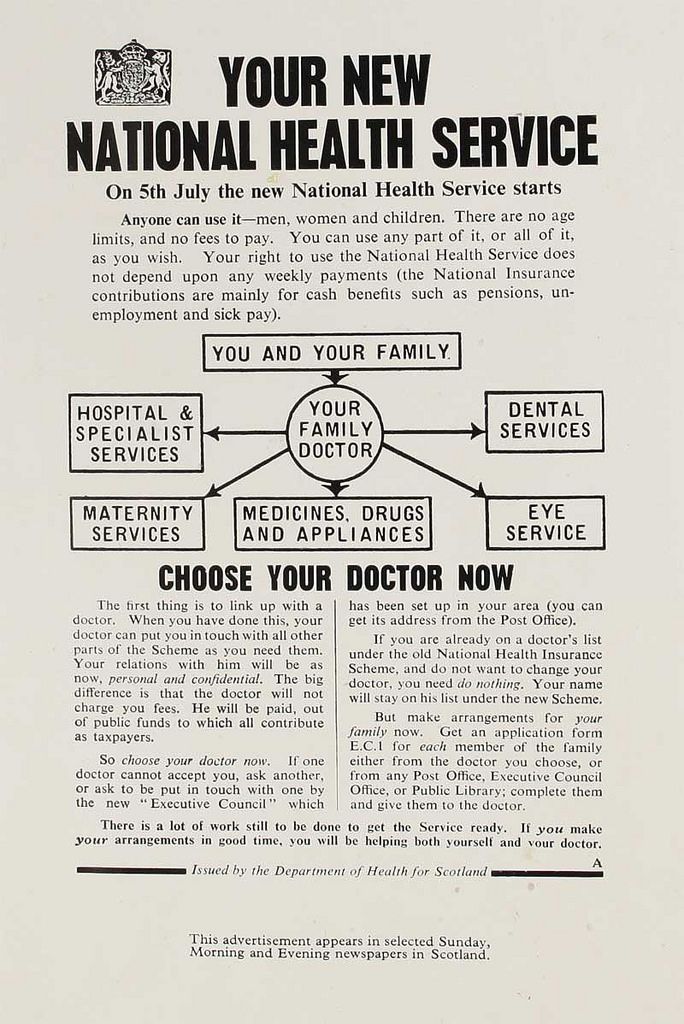

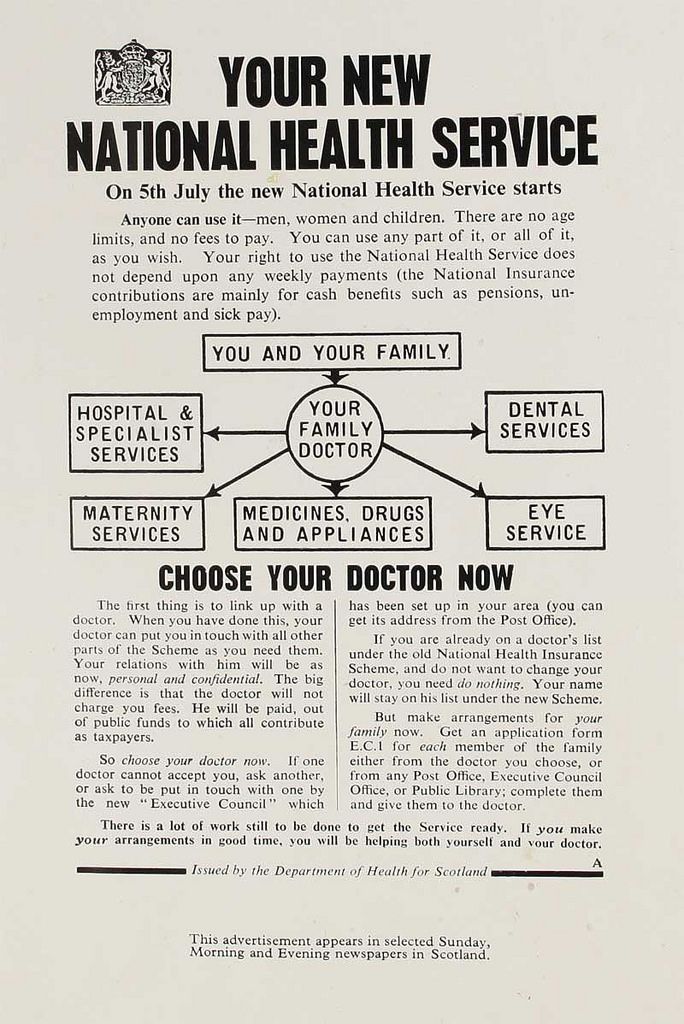

As the NHS turns 70, the issues of mental health and the availability of treatments for those who need them are important topics. Tragic stories in the media, often involving celebrities, and prominent campaigns, have led to growing public awareness of the importance of looking after the nation’s mental health. But it hasn’t always been that way.

Credit: National Archive

Mental health and physical health have taken very different journeys since 1948. It is only very recently that the two have started to gain a more equal footing in the health and social care landscape.

There is still much more to be done to ensure there is parity of esteem between mental and physical healthcare, and to break down the stigmas that prevent people with serious mental health problems from seeking or receiving the care they need.

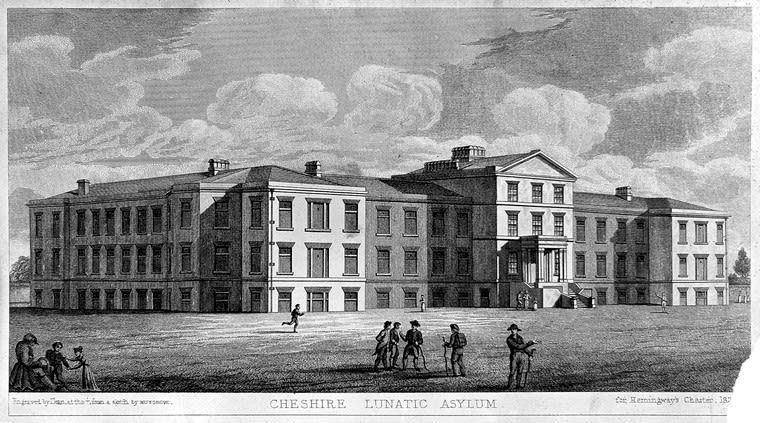

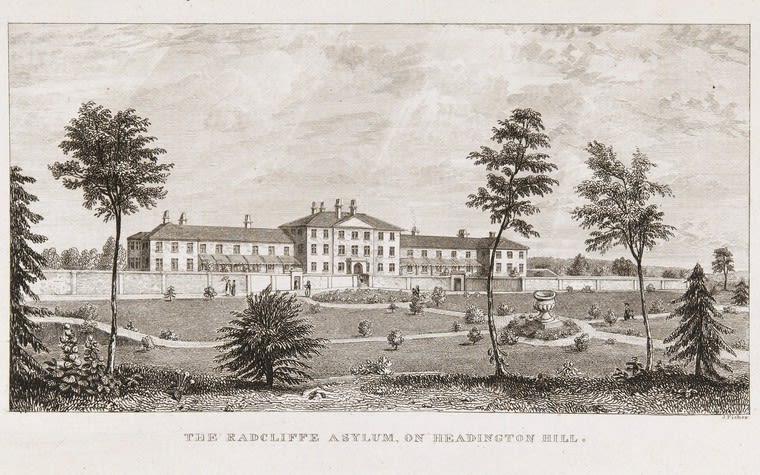

The Victorian legacy

Mental health treatment had remained largely unchanged in the years before the NHS was created. Methods and practices were old-fashioned, and mental health in general was shrouded in stigma. People suffering from mental health problems, and mental disabilities, were treated inside austere Victorian asylums, where they were kept apart from their communities and away from public view.

The language in official acts of Parliament relating to mental health and disability reflected the stigma. Words and phrases such as ‘lunacy’ and ‘mental deficiency' were regularly used.

While physical healthcare began to see medical advancements, improved treatments, and free access for all, mental healthcare stood still. This is despite the fact that interest in mental health had begun to grow during the Second World War, as servicemen and women returned home showing symptoms of conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

(Image credit: Wellcome Collection)

Radcliffe Asylum. Credit: Wellcome Collection

Radcliffe Asylum. Credit: Wellcome Collection

The Mental Health Act of 1959

In 1959, more than a decade after the NHS was established, Parliament passed The Mental Health Act.

Under the new Act, entry to hospital was to be decided on medical, rather than legal terms. There was also some attempt to integrate mental health care with the wider NHS. In 1961 the government declared the Victorian asylums that rose ‘daunting out of the countryside’ should be closed, and their patients cared for in conventional hospital wards, or within the community.

In reality, the integration of mental health services into the wider NHS was limited. It took many years for the nation’s asylums to be decommissioned – most weren’t actually closed until the 1970s.

Twenty years later

In 1983 The Mental Health Act was revised, and the issue of consent was introduced. Although people could still be detained under The Mental Health Act if they were at risk of harm to themselves or others, most people being treated for mental health conditions at this time had voluntarily sought help.

Into the community

Successive governments have encouraged community-centred care for people with mental health conditions. As far back as 1954, prior to The Mental Health Act, Winston Churchill’s government set up the Percy Commission to review the detention of people with a mental illness. The Commission argued that people should be treated within the community wherever possible, rather than within institutions, and that the barriers between mental health and the wider NHS should be removed.

Credit: Queen's Nursing Institute

After the 1959 Mental Health Act, community care was again encouraged, but change was slow to happen. Since then, the question of who should provide community-centred care, and who should cover the costs, remains unanswered.

In the late 1990s, the idea of community care provoked some anxiety among the public after a small number of incidents involving psychiatric patients were picked up by a largely unsympathetic press.

Credit: Queen's Nursing Institute

Credit: Queen's Nursing Institute

NICE mental health guidance

We published our first official NICE clinical guideline in 2002. This guidleine (CG 1) focused on schizophrenia, and provided guidance for healthcare practitioners about how best to treat people suffering from the condition. The guideline has been updated twice, and in 2014 (after its second update) extended its remit to cover psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management. This reflected our developing understanding of psychotic episodes and their long term relevance.

Since 2002, we’ve produced 80 pieces of mental health guidance on clinical, public health and social care topics ranging from the mental health of people in the criminal justice system, to social and emotional wellbeing in primary education, and the mental wellbeing of older people in care homes.

A common theme that runs throughout much of our mental health guidance is the need for a multi-agency approach when supporting people with mental health problems. By bringing together different agencies from health, social care, housing, education, employment, and benefits, people with mental health problems are more likely to be able to access the services they need to lead a normal life.

“Our mental health guidance is important for three main reasons. It provides the most authoritative review of the evidence for improving mental health; it embeds the best evidence-based practice into the NHS; and it exemplifies the multi-agency approach to managing people with mental health conditions.”

Using technology to treat mental health conditions

In 2008 the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme, which aims to provide psychological therapies for people with common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, was launched. IAPT services now treat 560,000 people per year, using a range of treatments including face-to-face therapy and digital therapies such as apps and online programmes.

As apps and digital technologies continue to advance their reach into mental health care, there has been some concern about how the public can be put in touch with safe and effective digital treatments that are known to have positive outcomes. To tackle this issue, as part of the IAPT programme, NICE has examined the effectiveness of different digital therapies.

So far, 5 digital therapy programmes have been evaluated by NICE and 2 of these have been recommended into the next stage of the evaluation programme. These are Deprexis and Space from Depression. Both are online programmes that use the principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to treat depression.

In 2017, 50% of people with mental health conditions were not offered alternatives to medicines – this is despite the fact that a quarter of those said they would have liked an alternative form of treatment (Community mental health survey, Care Quality Commission). Using technology to help treat mental health conditions could enable people to access treatment more quickly, cheaply, and efficiently than ever before.

A patient perspective

Portia Dodds was diagnosed with anxiety and depression at the age of 17. She explores her experience of accessing the system, how she benefited from treatment, and how services could be improved.

Initial help and diagnosis

“When I was 16 my mum noticed I was certainly not myself; I was coming home crying almost every day from school, kept very much to myself and started losing interest in things that I used to love. I was eventually referred to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), where I saw a psychiatrist and had weekly cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) sessions.

“During this time, I was also tested for and then diagnosed with high functioning Asperger’s. Unfortunately, as I was then 17 and had started taking medication, I was told they could not help me. After the age of 18, I would be progressed onto adult mental health services.”

Three suggestions for improving services

“Train GPs and doctors in noticing early signs of mental health issues - depression, anxiety, OCD, bipolar and other common issues - in all people. Not just young people and teenagers, but everyone.

“Create more localised CAMHS services to make them more accessible to people all over the country, and more support groups too.

“Allow 18, 19 and 20 year olds to stay within CAMHS rather than moving them onto adult mental health services, and make them more accessible when they go off to university.”

It’s not all about medication

“Medication is not a quick fix. I believe that a mixture of talking therapy and medication is a very good treatment and they have to come simultaneously.

"I saw a psychiatrist and two other mental health doctors for CBT as well as taking medication. As I responded well to these treatments, I saw no reason to differ from the plan I was given. I was spoken to and given choices, so I had some control of how I was treated.”

Changing attitudes

“There are a lot of conversations around mental health - in schools and universities, political debates, in the media - and so I think that attitudes are changing but this still needs to continue.

“Certain conditions are treated carelessly. For example, people sometimes say 'oh I'm so OCD', simply because they like a tidy house. On the other hand, there are some memes and gifs on social media saying 'you wouldn't tell someone with a broken leg to just walk, so don't tell someone with depression to cheer up’, which is encouraging.”

Seventy years on – what’s changed, and what’s to come?

In its Five Year Forward View, the NHS outlined mental health as a priority and vowed to work towards a better future that "dissolves the class divide" between physical and mental health. This marks a considerable change from the early days of the NHS.

*CQC

In 2016/17, nearly £12 billion was spent on mental health services in England (Mental health five year forward view dashboard, NHS England), and the NHS is on track to deliver 1,500 more mental health therapists in primary care by March 2019 (Next steps on the five year forward view, NHS England).

*CQC

In 2016, NHS England introduced waiting time standards for mental health services – these standards were based on NICE guidance recommendations. Since the waiting time standards were introduced, the percentage of people starting treatment within 2 weeks for a first episode of psychosis, as recommended by NICE, has increased from 64% to over 80% (NICE guidance and current practice report).

*CQC

Despite the achievements, mental health services can still be improved. According to a 2017 community mental health survey, 97% of respondents said they didn’t know who to contact with mental health concerns (Community mental health survey, Care Quality Commission). According to the NHS England Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, three quarters of people with mental health problems receive no support at all, while in some of the worst performing parts of the country, people can wait up to 124 days for treatment.

Mental health provision has certainly improved since the NHS was launched 70 years ago. Treatment options have increased and access to treatment has improved. Social barriers have been broken down, most notably those surrounding public attitudes. Mental health is being talked about more openly and positively than ever before - particularly by young people who will be a driving force for progressive change.

The NHS has clearly signalled intentions to improve standards for mental health care over the next few years. NICE will continue to support this work through its guidance, quality standards and advice.

*CQC

*CQC

*CQC

*CQC

*CQC

*CQC

For more on this topic, listen to the special NHS70 episode of our podcast NICE Talks. The episode features David Haslam, NICE Chair, Professor Mathew Thomson, a Researcher from the People’s History of the NHS research group, and Paul Farmer, CEO of Mind.