What is NICE’s severity modifier?

Since 1999, NICE acted as a trusted, independent guide in health and care.

We produce a range of guidance products to support practitioners and commissioners.

These include technology appraisals, which evaluate the clinical effectiveness of medicines, devices and diagnostic tools and their value for money.

We’ve published more than 1,000 technology appraisals so far. The vast majority of these (over 80%) are positive and recommend health technologies for use in the NHS.

Recently, there has been a lot of discussion about one particular aspect of our evaluations, called the severity modifier.

Some have argued that the severity modifier is holding back the introduction of new drugs and is denying people access to life-saving treatments.

So, what is the severity modifier? Why has NICE introduced it? And what impact has it had on the health and care system?

What is the severity modifier?

We carry out a lot of preparatory work before we produce a piece of guidance.

We introduced the severity modifier in 2022 as part of an update to our methods and processes.

The severity modifier is an algorithm that makes sure the methods we use to recommend treatments are appropriate for severe conditions.

It works by:

- Giving treatments for more severe diseases a higher weighting. This means that the health benefits of those treatments are valued more highly. This in turn means it’s more likely that we can recommend them for use on the NHS.

- In effect, raising the threshold for what we consider to be cost-effective for a treatment. This means that we can recommend more expensive treatments that provide significant benefits to patients with severe conditions. Without the severity modifier, these treatments might not meet our criteria for being cost-effective.

When we introduced the severity modifier, we sought to minimise the impact it would have on other effective treatments and care.

Each time NICE recommends a medicine, the money to pay for it must be found from existing budgets. As the NHS budget is finite, making a new treatment available means patients elsewhere in the system risk losing a treatment or care they are already receiving. This concept is often called ‘opportunity cost’.

Given the NHS's limited resources, any change to our methods must not create an additional cost burden to the system. So, we took an ‘opportunity cost neutral’ approach when introducing the severity modifier. In other words, the severity modifier does not displace more health technologies or care than our previous end of life modifier.

Why did NICE introduce the severity modifier?

We introduced the severity modifier to make sure that our technology appraisals continue to be fair and effective.

Prior to this, we used an end-of-life modifier.

The end-of-life modifier provided a higher cost-effectiveness threshold for medicines that improve patient outcomes in the last few months and years of life. It increased the likelihood that we would recommend such treatments, which were often for cancer.

The severity modifier benefits people with a broader range of severe conditions than the end-of-life modifier.

It means that our independent committees can now give greater weight to severe conditions and conditions characterised by a poor quality of life, such as hepatitis D and cystic fibrosis.

Neither condition would qualify for additional weighting under the narrower end-of-life criteria. It also benefits people with cancer conditions that wouldn’t have benefitted from the end-of-life modifier, such as those with glioma or leukaemia.

A recent example of this is Vamorolone, which became one of several non-cancer treatments we recommended following the introduction of the severity modifier.

This new treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is set to be available to around 1,700 people in England following positive final draft guidance.

More cancer treatments now being recommended

Through introducing the severity modifier, we’re also saying ‘yes’ to more cancer treatments:

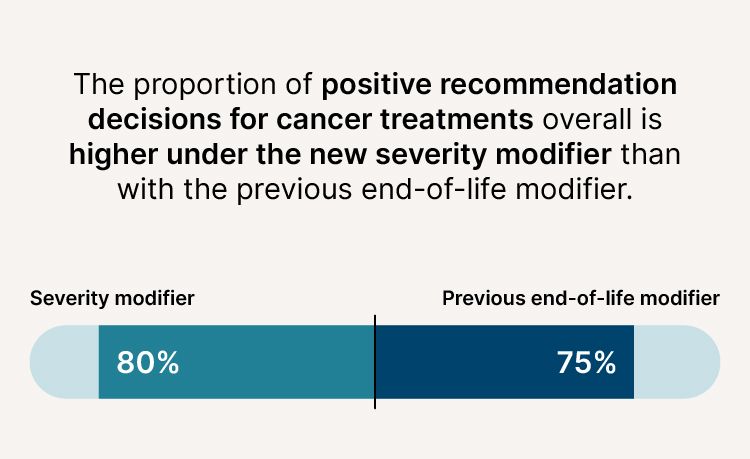

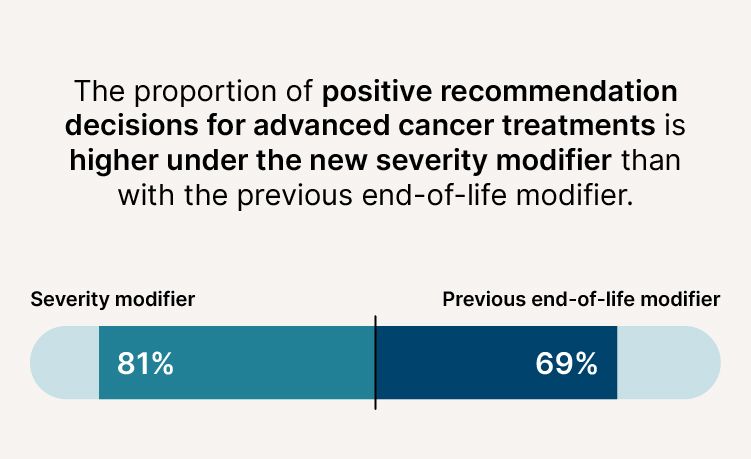

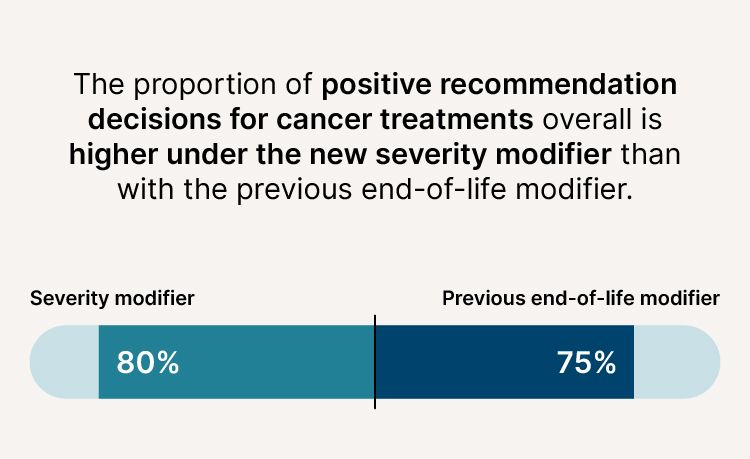

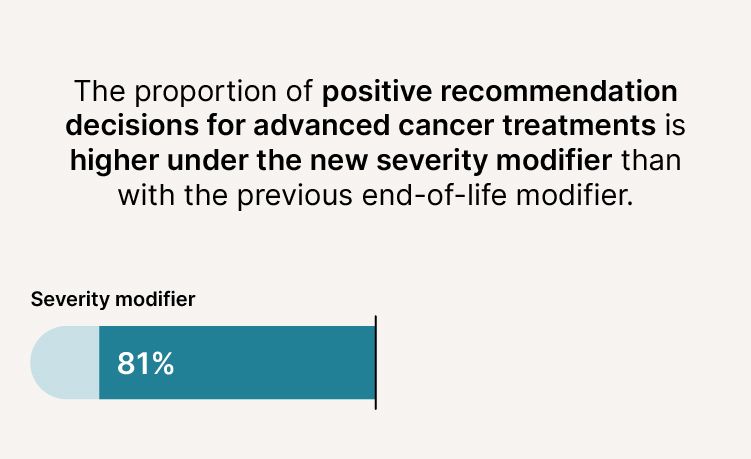

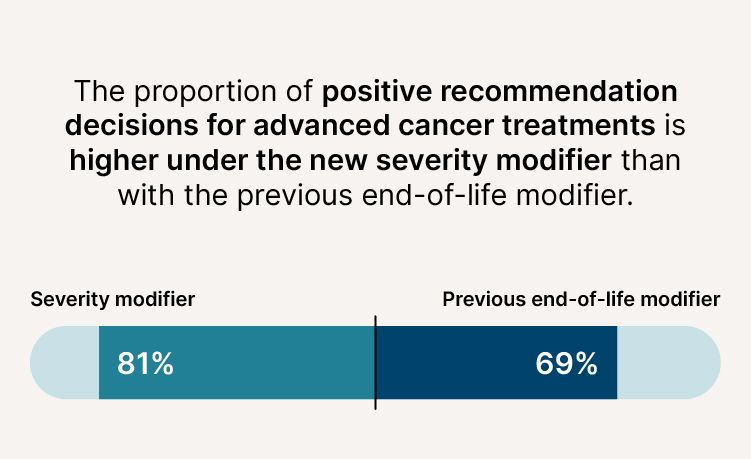

- The proportion of positive recommendation decisions for cancer treatments overall is higher (80% compared to 75%).

- The proportion of positive recommendation decisions for advanced cancer treatments is higher (81% compared to 69%).

We also introduced the severity modifier because it aligns with the values held by society.

Evidence shows that people in the UK highly value health benefits from treatments for the most severe diseases. And responses to 2 public consultations showed that stakeholders, including the life sciences industry, broadly supported the concept of a severity modifier.

We continually monitor our methods and processes. And as we do so, we’ve identified that further research is needed on society’s preferences on how much additional weighting to apply to health benefits for people with severe diseases.

Is NICE recommending fewer treatments now that it uses the severity modifier?

We commissioned a report from the University of Sheffield to evaluate our use of the severity modifier.

The report found that the new severity weighting is working as intended and expected.

This is because:

- It has been applied more widely than the end-of-life modifier it replaced.

- It has contributed to an increase in positive decisions for cancer medicines and non-cancer medicines that have dramatic and far-reaching impacts on patients. These include conditions such as cystic fibrosis, which would not have qualified for additional weighting under the previous criteria.

- It has remained opportunity cost neutral. In other words, it has not displaced other existing treatments from the NHS.

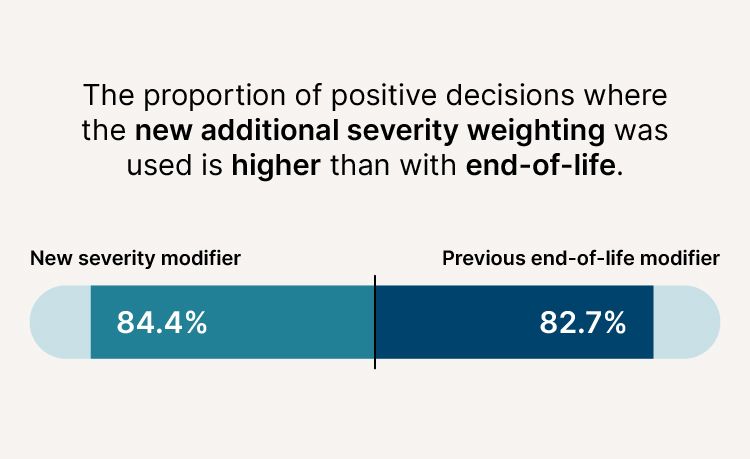

- The proportion of positive decisions where the new additional severity weighting was used is higher (84.4%) than with end-of-life (82.7%).

If the severity modifier is leading to more positive recommendations, why did NICE not recommend Enhertu?

Enhertu is a drug used for treating advanced breast cancer in adults.

Despite accounting for the condition’s severity by applying a severity modifier, and accounting for innovation and uncaptured benefits, the cost the NHS was being asked to pay was too high in relation to the benefits it provides for it to be recommended for routine use in the NHS.

It remains the only breast cancer treatment we’ve been unable to recommend for 6 years, and breaks a line of 21 positive breast cancer recommendations.

On the decision, Dr Samantha Roberts, chief executive of NICE, commented:

“We are extremely disappointed that talks to reach a price agreement that would have made advanced breast cancer drug Enhertu available to around 1,000 women in England and Wales have not been successful. As we’ve always made clear, the fastest and only guaranteed way to get medicines like Enhertu to the patients who need them is for companies to offer a fair price. We have done all we can to try and achieve that.”

Would NICE have recommended Enhertu if it used the previous end-of-life criteria?

Under the end-of-life criteria, there was a certain maximum weighting of our independent committees could apply.

This weighting was a quality adjusted life year (QALY) of 1.7. We use the QALY to estimate the health benefits of new medicines. The benefits, in terms of length of life, are adjusted to reflect the quality of life. One quality-adjusted life year (QALY) is equal to 1 year of life in perfect health.

However, not every treatment under the end-of-life criteria got a 1.7 weighting. And the average QALY weighting under end-of-life was less than 1.7. This means that some treatments for metastatic cancers would have got a 1.2 QALY weighting.

As a result, it cannot be presumed Enhertu would have got the higher weighting.

Other cancer treatments, including talazoparib for advanced metastatic breast cancer, have been approved under the new severity modifier criteria.

By downgrading terminal cancers to ‘moderately severe’, is NICE now less likely to recommend treatments such as Enhertu?

We’ve been monitoring the severity modifier, and produced a review on its use.

The review found there is no evidence that the change is making a positive recommendation for any treatment (including advanced cancers) less likely.

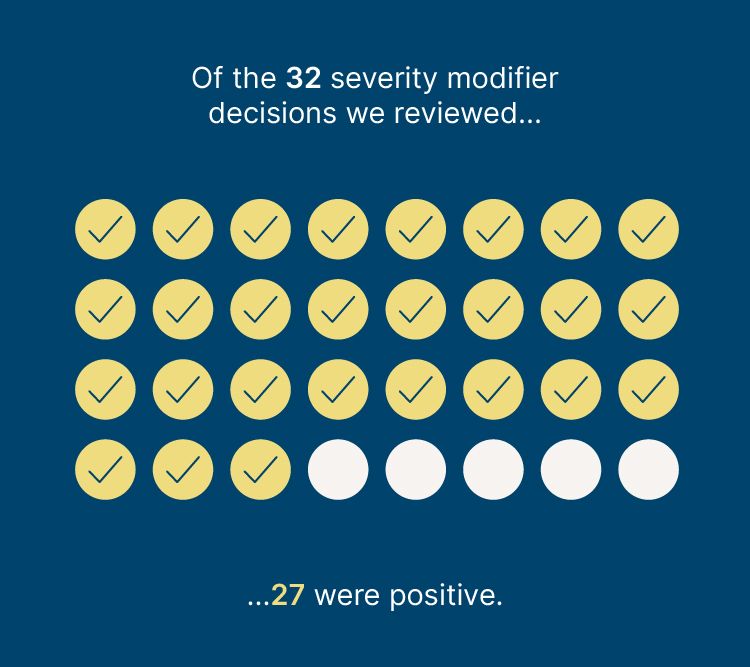

In addition, of the 32 severity modifier decisions we reviewed, 27 were positive. Only Enhertu for advanced breast cancer and pembrolizumab for relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma were negative.

How will NICE make sure that the severity modifier is fit for purpose and brings benefits to patients?

In September 2024, NICE’s board found that the severity modifier is working as intended and that no change is required. The severity modifier is therefore unlikely to change or be adjusted in the near future.

NICE’s board has agreed to continue monitor the impact of the severity modifier.

As part of this work, it will commission additional research into what society’s preferences are in terms of valuing medicines that treat severe diseases.